|

|

Cleveland and the Freeing of Soviet Jewry | |

|

Involvement in the Soviet Jewry

Movement

—

by Louis Rosenblum |

||

|

Political Action In the late 1960s, to check the growing wave of applications by Jews to immigrate to Israel, the Soviet government resorted to several strategies. Among these were the imposition of increased financial and procedural requirements for an exit visa, and criminalization of Jewish national feelings by arrest of persons possessing books on Jewish history or Hebrew language on charges of “anti-Soviet” activities. In regard to arrests, between late 1968 and late 1970, a number of “show trials” throughout the Soviet Union resulted in the sentencing of 46 Jews to the Gulag. The most publicized by the Western press was the Leningrad “hi-jacking” trial. Eleven people — nine Jews and two Russians — were tried for planning to seize a 12-seat plane and escape the country. They were arrested on arrival at the airport — the KGB had been monitoring their activities. They were charged with fleeing the country — a capital crime in the Soviet Union. Two were sentenced to death and the others given long sentences in special regime labor camp — the worst of the worst. The strong outcry from the free world at what was called ‘juridical murder’, caused the Soviets to back off a bit and commute the death sentences to 15 years in special regime camp. All of this did little to staunch the flow of applications to emigrate. By 1971, it was estimated that 250,000 Jews had sought permission to leave the Soviet Union. In the fall of 1971, the UCSJ decided, in convention, on a policy

shift to robust political

action, i.e., to promote legislation in the U.S. Congress that would

entail economic sanctions

against countries that restrict freedom of emigration. On January 1,

1972, I met with two

political pros (associated with the Washington Committee for Soviet

Jews). One of them,

Nat Lewin (a nationally prominent trial and appellate lawyer)

quickly produced a draft of an

amendment that could be applied to a foreign trade bill then

scheduled for renewal. The other,

Harvey Lieber (Professor of Political Science, American University

School of Public Affairs)

sketched out plans for preparation of position papers and

legislative tactics by his graduate students.

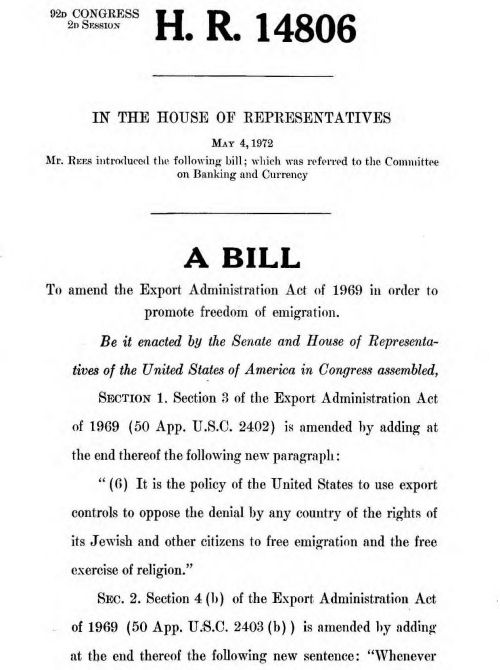

Our Southern California Council lined up California Congressman Tom Rees, a member of the Banking and Currency Committee, to introduce the legislation. Rees, on May 4, 1972, with several cosponsors, introduced in the House of Representatives HR 14806, A Bill to amend the Export Administration Act of 1969 in order to promote freedom of emigration.

During the rest of May, Lieber and his team together with Karen Kravette, the UCSJ Washington representative, line-up additional co-sponsors, improving prospects that the House Banking Committee would report out a renewal of the Export Administration Act with the Rees amendment attached. But it wasn’t to be. We were blind-sided by Jerry Goodman, director of the National Conference for Soviet Jews. Goodman — up till then silent — called to tell Rees he opposed the bill, because NCSJ’s policy called for “quiet negotiations” with the Soviets. Rees was dismayed and unsettled. The next day I flew to Washington, and together with with Representative Burt Podell (a strongly supportive Congressman from Brooklyn, NY), Harvey Lieber, and Karen Kravette, met with Rees and persuaded him to hang in. And we ramped up our efforts to muster votes in the Banking Committee. But damage was done. When the showdown came in mid-July, the bill went down two votes short of approval. Still and all, a precedent was set for introduction of a freedom of emigration bill with teeth. And, the American Jewish establishment, through its Soviet Jewry political arm, the NCSJ, affirmed a policy of “quiet negotiations” — shtadlanut. On August 15, 1972, the Soviet Union upped the ante for Jews wanting to leave. A ukase (a decree) was issued that imposed an exorbitant “education tax” on all Jews granted exit visas — in short, a ransom. This was a wake-up call for Congress. On October 4, Rep. Charles Vanik D-Cleveland, OH) in the House, and Sen. Henry Jackson (D-WA) in the Senate, introduced legislation that would deny most-favored-nation status (lowest tariff rates on export to the U.S.) to any nation that denies its citizens the right to emigrate. Over the next two years, President Nixon and his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger — intent on détente with the Soviets — did all in their power to derail the legislation. The UCSJ threw its weight into the struggle by firming up Congressional support: through Action Central, a rapid response group of forty regional political activists, coordinated by CCSA member Carol Mandel from Cleveland; through the UCSJ Washington office; and by feeding to the news media and Congress up-to-date reports of events in the Soviet Union, as transmitted to the UCSJ by Soviet refuseniks.

My personal involvement in this power struggle started in September 1972 with a visit to the White House, by invitation, to meet with Leonard Garment, Special Council to President Nixon. It concluded two years later with a trip to the Soviet Union to confer with Jewish activist leaders on ways they might influence the outcome of the tripartite, endgame negotiations among Jackson, Kissinger and Brezhnev. It was quite a roller coast ride. The Jackson-Vanik legislation passed in Congress with a veto-proof majority, in December 1974, and President Ford signed it into law January 3, 1975. In the 16 years between that time and the collapse of the USSR, more than a half-million Jews and tens of thousands of other persecuted minorities emigrated from Soviet Union. |

|

|

| © 2007 Louis Rosenblum |