|

1840 Petition for a Jewish Section of the City Cemetery |

|

The oldest document signed by our pioneer Jews and its story. |

|

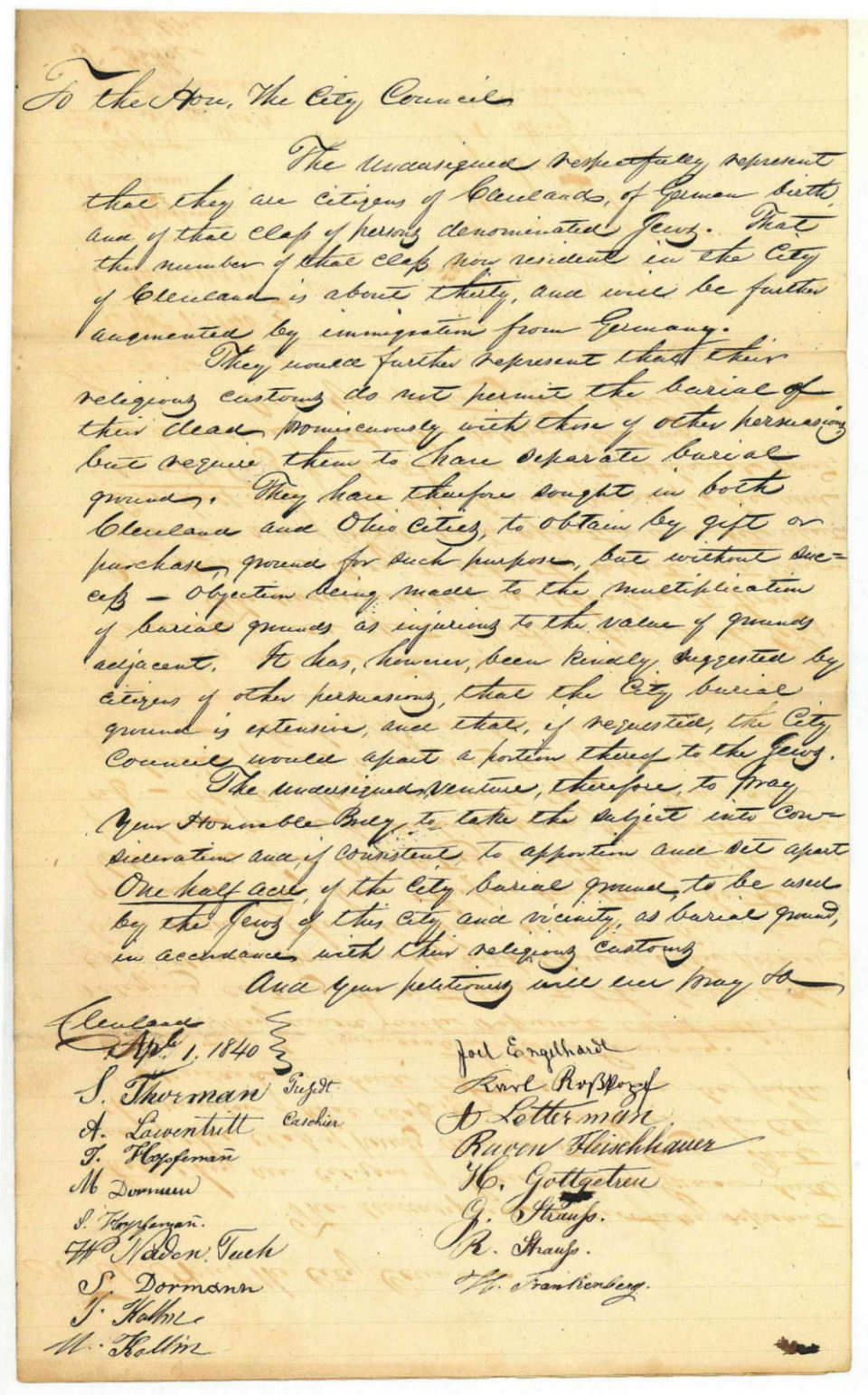

Introduction The April 1, 1840 Israelitic Society petition to Cleveland City Council for a Jewish section of the city cemetery is our oldest Cleveland Jewish historical document. Here's the historical background, the petition and the reason why City Council could not accept it. |

|

Historical Background |

|

Early in 1839 there were only a few Jews in Cleveland, notably Simson Thorman from Unsleben, Bavaria. After two years fur trading in Missouri, he settled here in 1837 and bought property. He wrote home, inviting relatives and friends to join him. On July 12, 1839, when the ship Howard arrived in New York from Hamburg, Germany with the Alsbacher Party of 19 Jews from Unsleben, Thorman met them and led 15 of them to Cleveland. He had a personal reason to be there, for Reichel (later Regina) Klein was in the group. A few months later Simson and Reichel would be engaged. Cleveland's Jews soon formed the Israelitic Society. (update 4/1/2025: An online Google book dated 1869 shows an Israelitic Society of Unsleben.) Thorman, only 28, was its leader. A Jewish burial ground was a priority, perhaps out of fear of child mortality, for there were no elderly among the Jewish settlers. (Infections took a terrible toll in those days of poor sanitary conditions, no vaccinations and no drug cures. One-third of children died before their 18th birthday.) The Unsleben Bavaria Thorman and others had left did not have a Jewish cemetery and would not have one until 1856. Its Jewish dead were laid to rest in the Jewish cemetery of Kleinbardorf, about 15 miles (a three-hour trip) to the southeast. But here there was no Jewish cemetery even a day (40 miles) away from Cleveland. Their cemetery would serve many communities. In 1840 Cleveland's Jews lived in what we now call the Gateway area. When community leaders learned that the city cemetery on nearby Erie (now East Ninth) Street would be adding eight acres of burial sites, they hired a 'scrivener' (a writer of legal documents and letters to courts) to write a petition to City Council asking for a half-acre Jewish section. The leaders and many members, seventeen in all, signed the document dated April 1, 1840. Strangers in a strange land, only 30 in a town of 6,000, they stepped forward to make a request to their new government. Their 1840 Petition is an example of vision, unity and courage. |

|

The document is about 9 by 12 inches. These slightly enlarged web-resolution images are displayed with permission of the Clerk of Cleveland City Council. The left and right ends of the lower image are blank and not shown. |

|

|

|

|

To the Hon, The

City Council

The

undersigned venture therefore to pray Your Honorable Body to

take the subject into consideration and if consistent to

apportion and set apart one half acre of the City

burial ground to be used by the Jews of this city and

vicinity, as burial ground, in accordance with their

religious customs. |

|

On April 7, 1840 City

Council referred the petition to its

Committee on Public Grounds. We can see their decision:

"The committee to whom this

petition was referred Report that it is inexpedient to grant

the prayer of the petitioners." The committee's ruling "inexpedient" is explained by city law. To make its cemetery a benefit for as many Cleveland families as possible, it had restricted the sale of burial plots to persons or families, with a six-grave limit. Allowing an organization to buy a large section would violate that policy. To grant the half-acre the Israelitic Society asked for would mean saying "no" to more than 80 requests for family plots. Perhaps the newly-arrived Israelites were not aware of this city policy, for no other organization petitioned for burial space.

The Israelitic

Society resumed its search for burial grounds and by

July found one: the Willet Street Cemetery.

•

The

Alsbacher Document

|